Mountain feats of the sisterhood

Drive for ecological and economic change leads to women's emancipation

In Jiabi village it seems that the sisterhood holds up at least half the sky, and a fair amount below it as well.

The village in question is located high up in the mountains of Dechen county, in the northwest of Yunnan province, and the women in question are a group that goes by the name of the Sorority.

Their participation in community affairs through the group has helped the village conserve its biodiversity and lift the living standards of its inhabitants.

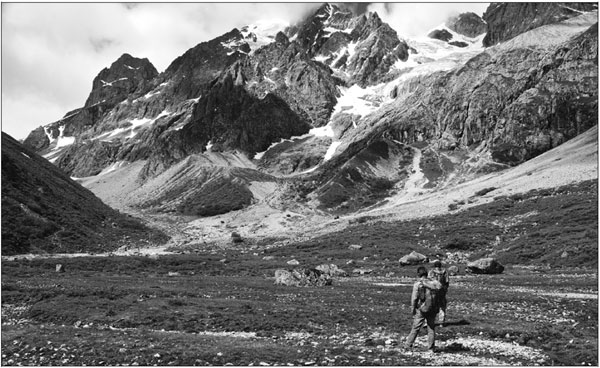

1. 2. 3. 5. 6. Dechen county, with an average altitude of more than 3,000 meters above sea level and which consists of a collection of snow mountains, glaciers, canyon, meadow and lakes, has kept abundant species and is a representative of Yunnan province's rich biodiversity. 4. Local villagers tend to fields of vegetables. Photos Provided to China Daily

It is something that excites Yin Lun, an ethno-ecologist who has done fieldwork in ethnic Tibetan communities in the eastern Himalayas, where the county is located, for 15 years.

In fact, so excited is Yin with the project that it occupied a large chunk of a speech he delivered at the Paris Peace Forum in the French capital that ran from Monday to Wednesday. More than 100 projects presented at the forum were selected from more than 700 candidate submissions from 115 countries.

The annual forum was initiated by French President Emmanuel Macron last year to discuss and debate global governance issues and solutions to problems in fields such as peace and security, development, environment, new technologies, the inclusive economy, culture and education.

Protection of biodiversity, an issue to which China and France attach great importance, was one of the forum's most important topics this year.

The two countries co-issued an initiative on biodiversity conservation and climate change on Nov 6 during a three-day visit that Macron made to Beijing.

In it the two reiterated their determination to ensure the Paris Agreement is implemented and to jointly work on preparing for the 15th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity which, will be held in Kunming, Yunnan's capital, next year.

Among the many academics committed to protecting biodiversity and tackling climate issues is, Yin, 45, a researcher at the Yunnan Academy of Social Sciences, who is from the Bai ethnic group and whose wife is an ethnic Tibetan. He is one of few people who have entered the field by observing the traditional cultural legacy of ethnic groups in China.

In Jiabi village the Sorority's counterpart for men is called the Arrow Association.

The original goal of both organizations was to organize and raise funds for village entertainment, and it later branched out to provide public services such as road building and clearing.

The Sorority was founded more than 20 years ago, and the values that the Arrow Association espouses have been around for many decades, being passed down through the generations. It was only after the Sorority was founded that the Arrow Association became more of a formal group.

The two organizations support each other with labor and funds, said Renchen Phuntsok, whose wife Choszom has been in charge of the Sorority for more than a decade. She speaks only Tibetan, and her husband interpreted for her when she spoke to China Daily.

Apart from Choszom, six other women, each from one of the village's 30 families, take turns shouldering the responsibility of things such as organizing group events, bookkeeping and handling money.

The members help each other arrange weddings and funerals and build their houses, the latter of which may take several years. As they do all of these things they are obliged to follow rules such as wearing traditional Tibetan attire during festivals and rituals. Great store is also put by punctuality, and anyone who is late for an event is fined.

Yin went to the village 15 years ago to do research on his doctoral thesis, on the Tibetan tradition of polyandry, in which a woman has more than one husband. He lived with Renchen Phuntsok's family and in busy times helped them with the farm work.

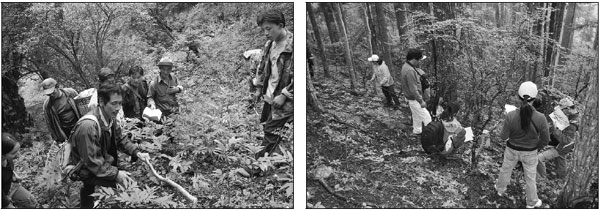

He also encouraged villagers to carefully note the characteristics of the local environment with their own eyes and ears. In so doing they were able to record even the subtlest changes in nature over half a century.

In groups, men focused mainly on climate change, natural disasters and building traditional dwellings that requires using natural resources, and women worked on assessing forest fungus resources and controlling the excessive collection of matsutake, or pine mushroom.

The project was carried out under the auspices of the Center for Biodiversity and Indigenous Knowledge in Kunming, for which Yin served as a project assistant when the project began. He is now director of the center's project management department.

He recalls the first years in the village when the center helped villagers build irrigation systems and install plumbing and gave them financial support so they could buy and install solar water heaters. In that enterprise the women gave full play to their forte of being able to identify high-quality products and beat down the prices that suppliers were asking.

They also did well as forest rangers, catching those engaged in inappropriate wood chopping and medicinal herb digging, he says.

Yin says one of his prime goals was to encourage locals to take the initiative in such projects. He took them to Dali, Yunnan province, to see how the locals bred chickens and pigs, how they ran handicraft workshops, and how the community worked to support one another.

In 2013 his team set up a microcredit loans project to finance community affairs in Jiabi village and to promote the economic well-being of its inhabitants. Yin realized the women had the skills and self-discipline to manage the Sorority's accounting, and he and his team let them take charge of the program.

The women welcomed that because it meant that any interest earned from lending money could be reinvested in the community, and they were able to use a traditional way of covering risks, having three people act as guarantors. This has since been reduced to one person.

Last year Yin set a kind of integrity test for the Sorority, asking it to return the capital that had been given to it, and without hesitation the group paid back the money. The funds were then invested in another project, supporting the work of local veterinarians who had to deal with the outbreak of livestock diseases.

A second round of microcredit loans project operated by the Sorority will start from next year, Yin says.

Choszom says the Sorority has paid a lot of attention to disadvantaged families, and they are its main beneficiaries.

However, as people's lives improve and modern technology floods into the village and makes organizing events easier, the awareness of local traditions has faded, Renchen Phuntsok says. This is especially so among young people, and fewer women are devoted to Sorority now, he says.

Dechen county, with an average altitude of more than 3,000 meters above sea level and which consists of a collection of snow mountains, glaciers, canyon, meadow and lakes, has kept abundant species and is a representative of the province's rich biodiversity. More than 70 percent of its land is covered by forests.

However, locals nowadays experience increasing extreme weather events such as storms, droughts, high temperatures and landslides, which are also borne out in meteorological data.

The herders, who dress more lightly now because of warmer weather, report seeing not only the earlier maturation of grass on grazing land, but also the emergence of flies and mosquitoes on alpine pasture, Yin says.

Renchen Phuntsok says watermelons can now even be grown, in an area where it was once too cold for such a crop, and there is less water for irrigation, especially in winter.

Despite this, the ethnic Tibetan communities have been using their traditional wisdom and passing down through the generations to protect the environment and prevent the diminution of biodiversity.

Although hit by the ideas of modern life to varying degrees, local Tibetans in the villages of Jiabi and nearby Hongpo maintain that their mountains, lakes and rivers are sacred and believe that to gratuitously fell trees and hunt is to risk the wrath of the mountains and the ensuing punishment of climate disasters.

It is of the awareness of the frail ecosystem in a harsh climate and hardy geographical conditions that locals' reverence for nature is born. It also partly explains why biodiversity usually comes with cultural diversity, as is shown in the cases of the Himalayan and Amazon regions, and also Mexico, Yin says.

Thus between 2009 and 2013, Yin conducted a program with monks in the mountains in which the locals paid little care to the natural surroundings. The aim was to raise the latter's awareness of the damage humans can cause.

Yin and his team have also organized more than 20 experts on Tibetan medicine to study the impact of climate change on 368 kinds of Tibetan medicinal herbs in mountains, and worked with monasteries and monks trying to plant about 20 kinds of endangered medicinal herbs and plants.

Dondrup, a local official who was among Yin's earliest illuminators of indigenous culture more than a decade ago, says Yin has turned daily routines that villagers take for granted as wells as traditions they are obliged to follow, into practical academic research that combines climate change theories with local realities.

Yin's work complements decades of governmental efforts to improve locals' living standards and protect the environment, Dondrup says.

Yin received his master's degree in social anthropology studies at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales in Paris and a doctorate at Minzu University of China in Beijing.

To accomplish the program work he used to spend half of his time in the villages, sometimes for months on end, first as a primary schoolteacher and then as an interviewer as he started fieldwork that would take him to being an NGO project leader, and finally being treated as one of the villagers.

Dondrup was impressed by how quickly Yin became acquainted with the locals, within a month, and by how meticulous he was with his work.

Yin, now a father of a 2-year-old daughter and a 6-month-old son, and a frequent traveler for work, has turned his main focus to fundraising and project planning, although he still goes to meet his friends in the countryside every few months.

"Now I try to leave more things for the locals to accomplish. My ideal is to be an assistant who writes down a project application, discusses with them the big ideas and lets them do the rest. I'd call myself a loser if after so many years I still had to do the job on my own."

Traditional knowledge, local beliefs, customary laws and community protocols regarding biodiversity provide a social and cultural light in which the challenges brought by climate change can be dealt with, he says.

"Their traditional knowledge and experience may not seem scientific, but they do represent a shining beacon of wisdom."

In rural communities where facilities and financial support for environmental protection are hard to access, community-based methods consistent with traditional knowledge and the scientific knowledge of the locals are the most grounded, he says.

Over the years, Yin has also had the chance to talk to indigenous peoples and representatives of local communities around the world about his experience, because "local adaptation strategies of different regions also contain a global perspective".

He has built connections with similar action programs run in communities of indigenous peoples in Africa, Australia and Latin America and has been planning to form a research network among the indigenous peoples and ethnic minorities.

In 2011 a group of Cambodians, Thais and Laotians visited Dechen county, and in 2015 it was the turn of Dechen people to visit Cambodia and Thailand.

These folk, who live upstream and downstream of the Lancang River, or Mekong, got to know each other.

Back home, an exhibition of photos showing the downstream in the eyes of the participants from Dechen was held, and Yin, who was one of the organizers, was delighted when he heard from one of the participants that locals had pledged not to dump trash into the river because there were people living there.

Writing by Fang Aiqing (China Daily); editing by Wang Jingzhong