Oldest evidence of parasites discovered

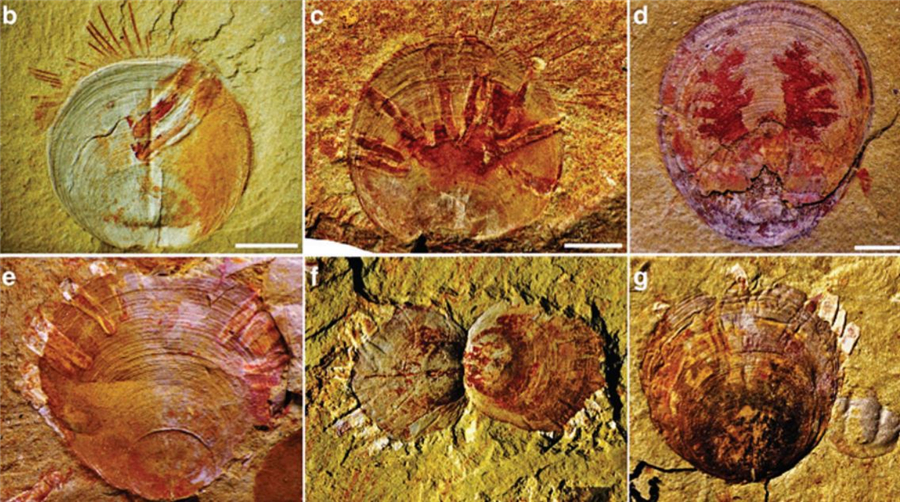

Markings from the tube-shaped parasites are clearly visible on the fossilized shells. Photo provided by Nature

Scientists in China have unearthed fossil evidence of a 512 million-year-old worm-like creature that restricted the growth of marine invertebrates by feeding off their meals, providing the earliest known evidence of a host-parasite relationship.

The ancient organism was a kleptoparasite, which means it stole food from its host. Etchings from the tube-shaped animals were preserved on the fossilized shells of brachiopods in the Maotianshan Shales, a paleontological hot spot in Southwest China's Yunnan province.

The creature lived during the Cambrian period, a time before life had colonized dry land. Microscopic plants, microbial mats and invertebrates with exoskeletons, including trilobites and arthropods, were some of the dominant forms of marine life, along with shelled organisms known as brachiopods that appeared similar to, though are distinct from, clams and other mollusks.

Authors of the study, which was published in the journal Nature, posit that the emergence of such parasites could have played a role in ushering in the so-called Cambrian explosion, a supercharged acceleration in the diversification of lifeforms that occurred half a billion years ago.

Zhang Zhifei, a paleobiologist from Northwest University in Xi'an, led the study into the fossils, along with researchers from the Swedish Museum of Natural History and Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia.

Zhang unearthed hundreds of brachiopod shells that had been encrusted with the worm-like animals. Small brachiopods had evidence of just a few of the animals etched onto them, while larger shells had been weighed down with a dozen or more.

But the etchings alone were not evidence enough of a parasitic relationship. The worm-like creatures could just have been a minor nuisance, anchoring themselves to the brachiopods to hitch a ride.

Some creatures of different species take up sustained relationships that are passive, or even symbiotic, where both organisms benefit from one another. A true parasite, however, must inflict a clear negative biological effect on its host.

The eureka moment came when the team established that brachiopods that were free of the creatures grew to a much larger size. This suggests that the tubular organisms shared meals with the brachiopods, limiting their nutritional intake. Furthermore, all of the tube etchings were oriented in the same direction on the brachiopods, towards the area of the shell where feeding intake occurred. Animals that steal food from a host are known as kleptoparasites.

"Brachiopods with encrusting tubes have decreased biomass, indicating reduced fitness, compared to individuals without tubes," the authors said in the study.

The researchers believe this is the earliest evidence of a parasite-host relationship ever discovered. The emergence of such parasites may have had a notable impact on the evolution of lifeforms at the time, and contributed to what is known as the Cambrian explosion, or radiation.

"Their emergence may have played a key role in driving the evolutionary and ecological innovations associated with the Cambrian radiation," the authors said.

Earlier this year, a 518 million-year-old fossil of a tube-dwelling animal found at the Maotianshan site provided the earliest known evidence of an organism that evolved to lose body parts, a process known in biology as "secondary loss".

Editor: John Li